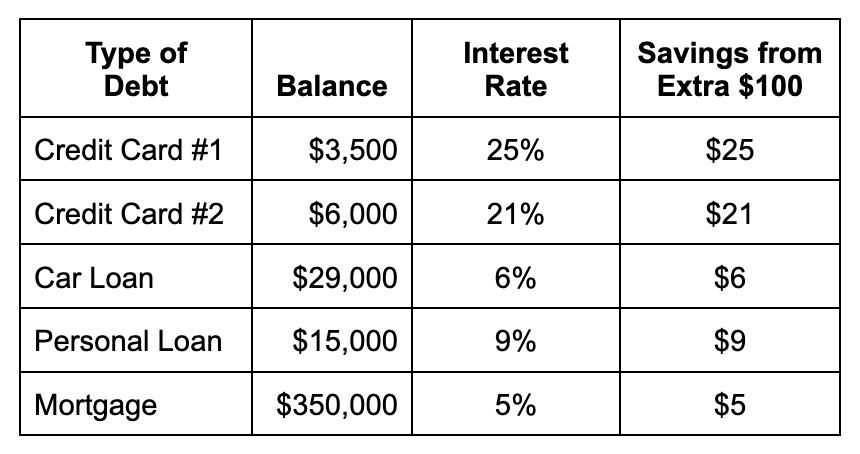

I continue to come across a surprisingly common misconception when I’m talking to people about finances and/or teaching my class. The misconception arises in the context of paying down debt and where folks should put any “extra” funds they may have available. I’m going to use the following theoretical example of someone who currently has the following debt and has an “extra” $100 to apply to that debt (beyond making the minimum required payments on all of their debt).

The misconception is that the balance of the debt matters when thinking about where to apply any extra available funds. A lot of people have heard about how much interest they can save by prepaying on their mortgage, so they decide to pay the extra $100 toward their mortgage each month. There’s also a subset of people with this misconception who mentally set aside the mortgage as a “different” kind of debt; they then look at the remaining debt and decide to put the $100 toward the car loan because, after the mortgage, it has the highest balance. In both cases, their thinking is that the debt with the largest balance is generating the most dollars of interest each month, so they should put that extra $100 toward the largest balance.

The first part of that statement is accurate, your balance certainly matters when you are contemplating how much total interest you are paying. (Which is why you want to keep your total debt as small as possible.) But the conclusion that therefore you should put the extra $100 toward that highest balance debt is incorrect. The best way I’ve found to illustrate this is replicating that table, but adding another column that illustrates the savings from the extra $100 in payment.

The key is thinking about the $100 extra payment itself, not in the context of the balance of the debt. If you pay an extra $100 towards a debt with a 25% interest rate, you will save 25% of the $100 or $25 (assuming those are annual interest rates, that’s what you would save after one year). Barring any other factors (for example, private mortgage insurance on a house loan where paying it down might eliminate the extra PMI), you should always pay the highest interest rate debt first (no matter the overall balance of the debt).

Note that you always want to make the minimum payment on all of your debt so as to avoid penalties; this is just referring to any extra you have to devote to your debt.

For folks who are working under the misconception, they would likely order these debts from greatest to least balance, and pay extra on the mortgage, then the car loan, then the personal loan, then credit card #2, and finally credit card #1. When the best strategy is the exact opposite.

Note that another popular method of debt repayment, often called the snowball method, is to pay off your lowest balance debt first, then work your way up. If that is the only possible way you can manage to do this (due to the behavioral aspects), then you should do that. But I’m going to assume that as a rational adult you will be able to choose the method that allows you to pay off your debt using the least amount of money and in the quickest way possible.

This method is sometimes called the “avalanche method”, but I prefer to simply call it the best method :-). Apply any extra money you have to your highest interest rate debt first. Once that debt is paid off, put the extra toward your next highest rate debt. Continue that process until you don’t have any debt remaining.

One Caveat: if you have a low interest rate of around 4-5% or less, it can often make sense to invest the extra you have available rather than to pay down your debt faster. This comes up frequently these days as so many people were able to lock in historically low mortgage rates of below 4% (and sometimes below 3%). While it’s not “bad” to pay extra on those, the optimal decision for most people would be to just make your minimum mortgage payment and invest the extra, under the assumption that you can achieve a higher return on your investment than the return you get by paying off such a low interest rate loan.