There are many articles/posts/discussions in the media (traditional, new and social) that use the words “middle class.” Similarly, in the financial literacy for educators class I teach, the words “middle class” often come up in our discussions. But, as with so many things these days, people rarely define what they mean by the term. While I think most of us have a sense of what we mean when we say “middle class”, I also think many of us don’t have a particularly good handle of what truly is middle class. As a result, many folks who think they are in the middle class may not actually be in the middle class. And it’s not because they don’t make enough to be in the middle class, it’s because they make too much (and are actually in the upper class).

There are many ways, of course, to define middle class and, depending on how you define it, you may come to different conclusions. I think this article from Smart Asset is worth thinking about. They use Pew Research’s definition of middle class, which is if you earn between two-thirds and double the median income in your area you are in the middle class. While you may prefer a different metric, I think that is reasonable-enough definition to put some context around this discussion.

Since I live in Colorado, and the class I teach is for Colorado educators, I’ll take a look at Colorado’s middle class using this definition (using the 2022 U.S. Census one-year American Community Survey data). (You, of course, can look at your own state.) Note that this is household income, so if you have a partner it includes both of your incomes.

- Colorado Median Household Income: $89,302

- Lower Bound of Colorado Middle Class: $59,529

- Upper Bound of Colorado Middle Class: $178,604

I think many folks may find these numbers a bit surprising. For example, many (not all) people in my class have household incomes that are near or above that upper bound. This means they are either in the upper middle class or actually in the upper class (using this definition). Yet most of them (and likely many of you reading this) don’t feel like they are in the upper middle class or upper class. I think there are many, many reasons for this, but one of them is that many of us spend most of our time with other people who make about the same amount as we do (or more). We have a very skewed perception of how our income compares to the median income. And, not for nothing, when you look at this in the context of global income, the disparity is even greater, as almost everyone in my class (and likely reading this) is in the global upper class.

I think this is especially prevalent in public education, as many of us feel we are underpaid. When you compare educator salaries to those with similar levels of education and experience, that is often the case. But I think it’s possible for both of the following to be true:

- Educators should be paid more.

- Educators (in many places) make above-average (median) incomes and that income when combined with a partner’s income puts them at least in the upper middle class.

(Note that in Colorado, like many states, educator salaries vary widely. So there are certainly districts where the average educator is not making such a good salary. But there are many, many districts where they are.)

There are two reasons (at least) this is important to think about. First, I think it’s helpful to have better context when thinking about your own personal finances. While comparing to others is rarely helpful, many people do. Having a better sense of what others actually make can perhaps provide a better perspective on what you make.

Second, I think it’s really important in the context of public policy. When we are discussing (and voting on) public policy, many folks who are actually in the upper class (or at least upper middle class) feel like they are in the middle (or lower middle) class, and therefore have an incorrect perception of the rest of society and who perhaps needs extra help (and who really doesn’t). Everything from tax policy to safety net programs need to be considered in the context of people’s actual incomes and situations, not on what we feel like our situation is. When we support or oppose certain policies, we should be doing so using actual data, not what we feel.

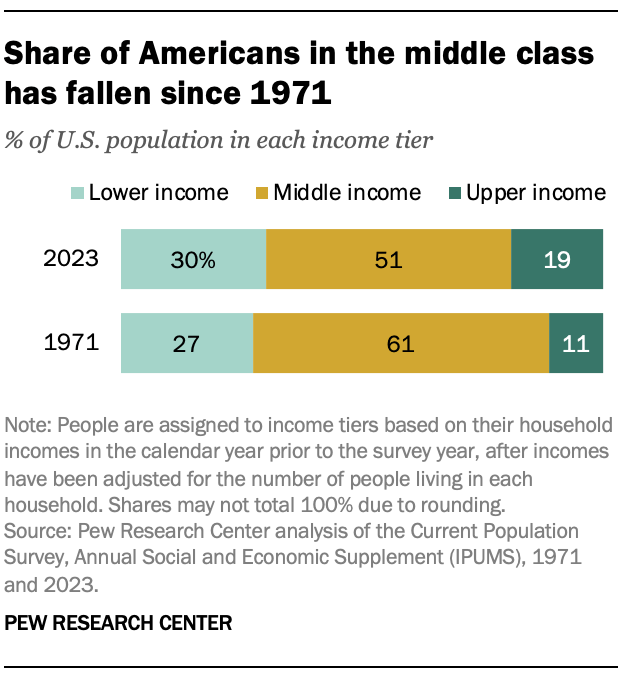

As an additional example of this, most people feel like the middle class is shrinking in the U.S., and they would be correct (at least using this definition). But what would likely surprise them is that more of the shrinkage is coming from people moving into the upper class than folks slipping into the lower class.

So next time you are thinking (complaining?) about your financial situation, or next time you are discussing public policy, consider grounding your thinking in a more realistic context than simply how you feel about it. Feelings are definitely important, and I’m not suggesting that many folks are not feeling stress and struggling. They are, and I’m not trying to minimize that. But I don’t think it does any of us any good to go down the road of using “alternative facts” in order to justify our feelings.