Note: This post is going to assume a lot of privilege. It’s not going to address the very real issues of income inequality and systemic disadvantage, as those are a bit beyond my wheelhouse (although I do have pretty strong opinions about policy changes we should make that could at least help address those issues). So I in no way mean for this post to imply that “Everyone can do this!” They can’t. And I’m not trying to “brag” about our particular situation. But many of the people who read this blog do have a fair amount of privilege and can perhaps do some version of this, so please read this with that context in mind.

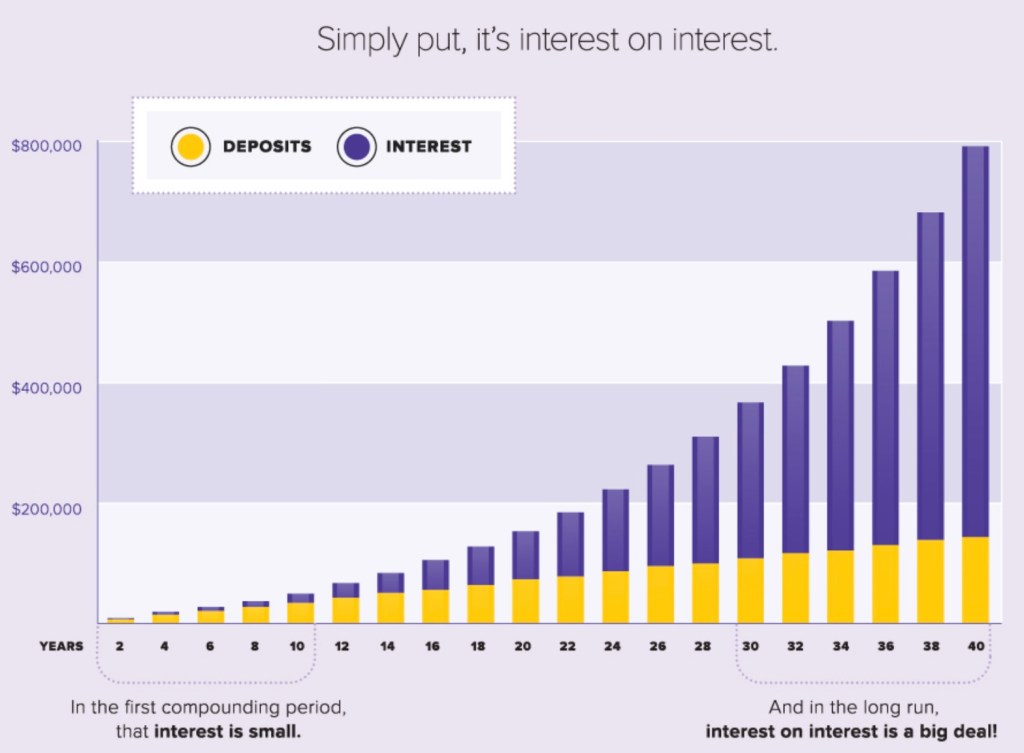

Humans are, in general, linear thinkers. We just have a hard time understanding exponential growth and, as a result, don’t understand the power of compound interest. This comes up frequently in my financial literacy for Colorado educators class, where participants often say, “I wish I had known this earlier!”

I was reminded of this again in the most recent section of the class I taught. One of the articles I have them read is this blog post I originally wrote back in 2017, which talks about the opportunity that working teenagers have to contribute to a Roth IRA if they are able to. As I noted in the original post, this assumes, of course, a fair amount of privilege; that a teenager has the ability and opportunity to work, doesn’t have to contribute to help the family pay the bills, and that the family itself has the wherewithal to perhaps provide an “employer match” for their teen. One of the participants in the class noted that my daughter already had way more retirement savings than they did (even though they were much, much older).

Last year I wrote a related post about the advantages of young people continuing to live at home for a while as a young adult. Again, this assumes a lot of privilege (and, of course, some people have strong opinions about whether it’s good for young adults to live at home). That post demonstrates the power of compound interest through various potential scenarios. And I recently ran across this old post from Nick Maggiulli titled, “Go Big, Then Stop” that demonstrates the same idea. As Nick points out, and as we discuss frequently in my class, it’s really important to find the right balance between living now and saving for the future. But that’s part of the beauty of young adults starting early (when they are working teens and much of their needs are met by their parents), and/or continuing to live at home for a while when they begin working full time (and their living expenses are greatly reduced due to not having to pay for housing). In effect, they are able to hypersave for the future without sacrificing their current spending. This is due, of course, to the parents making up that difference which, again, is only able to happen due to privilege.

I thought a good demonstration of this concept would be to write a followup to that original “working teens and Roth IRAs” post from 2017 describing our daughter’s current situation. Our daughter is currently 25, has graduated college (with no student loan debt) and is working full-time (for a public school, so contributing to a defined-benefit pension plan), makes a decent (but not great) salary, and is currently living at home. This has allowed her to continue to build on that early start on retirement savings mentioned in that 2017 blog post (including frequent “employer matches” from us). Here is her current financial situation.

- Approximately 8 years of service credit in her pension plan. She’s on PERA Table 7, so if she continues to work in a PERA-covered position until retirement (impossible to know at this point), she would be eligible to retire and receive a PERA benefit of 87.5% of her Highest Average Salary at age 52.

(She could also retire at 50 with a reduced benefit of 70.3% of her Highest Average Salary. Or she could choose to stop working and delay taking her pension benefit until a later age and use other money – like what’s in her pre-tax 457 and her taxable brokerage account – to live off of until then.) - She currently has six figures in her retirement accounts, which include a Roth IRA, a Roth 401k, and a (smaller) pre-tax 457.

(Because she is living at home and we are providing an “employer match”, she can contribute a large portion of her paycheck to her retirement accounts. We are also currently funding her yearly Roth IRA contribution from the remaining balance in her 529 plan). - She currently has five figures in her taxable brokerage account.

- She currently has five figures in her HSA account (and is maxing out her contribution each year, again with a match from us).

- She has no debt (she drives our second car).

Because of her early start and her privilege (along with some really favorable market returns), she is in an incredible financial position. When she moves out on her own she’ll be in a position where if she needs/wants to spend all of her earnings on her current lifestyle she can without sacrificing her future needs. We certainly hope she’ll continue to contribute some to her retirement accounts, but she won’t have to because she already has enough in place that, with the help of compound interest, she’ll have more than enough for retirement (especially if she sticks with PERA-covered employment). (And the reality is also that she will eventually receive a decent inheritance from us as yet another byproduct of her privilege, which is another safety net for her.)

The reason for this post is threefold. First, to show the incredible opportunity of starting early (and compound interest). Second, to point out the role that privilege plays in all of this. Third, and most importantly, to show folks the possibilities for their children if they also have the opportunity and the privilege. There’s nothing “magic” in what we’ve done; it’s just a combination of some basic financial knowledge (and fortuitous market returns), starting early, not forcing her to move out after college, and lots of privilege. One way to you could think about this is that we are “front-loading” some of her inheritance now (living at home, matching her contributions) in order to de-stress her life (both now and in the future). I talked about this some in Episode 17 of my podcast, the strategy of giving some of their eventual inheritance to your kids at an earlier time in their life when it will make much more of a difference than if they receive it at the age they will be when you die.

Can everyone do this? Absolutely not.

Will everyone who can afford to do this think it’s a good idea. Absolutely not.

But if you are in the position where you can afford to do this, I think it’s worth taking the time to really think through your options. How much is it worth to relieve the daily money stresses from your child(ren)’s life(s)? What’s the right balance (for you) between front-loading some of their inheritance or leaving it to them when you die and they are in their 50s or 60s? There are obviously a lot of personal values involved in this decision and you have to figure out the right approach for you. Warren Buffett has said, “I want to give my kids just enough so that they would feel they could do anything, but not so much that they would feel like doing nothing.” I’m not sure if this approach aligns exactly with that, but it feels pretty close to me.

Congratulations! You really set your daughter for success. I plan on using this plan as a template for my 17 year old when he graduates college in 5 years.

Thanks for posting this article.

LikeLike