The topic of Roth conversions and filling up your tax bracket came up at this month’s meeting of the Southern Colorado Mustachian group. While I’ve previously written about the related topic of capital gains harvesting, this is a bit different and has some interesting nuances.

What is a Roth Conversion?

A Roth conversion is when you take money that is already invested in a traditional, pre-tax IRA/401k/403b/457b and “transfer” it to a Roth IRA/401k/403b/457b. Current tax law allows you to do this at any age with no penalty, but it is a taxable event. The amount you convert counts as taxable income in the year you do the conversion.

This whole idea may seem counterintuitive for folks. The reason we put money in traditional retirement accounts in the first place was to avoid paying taxes now and deferring the taxes until much later when we withdraw the funds (hopefully in retirement). Why would someone want to reverse that and pay the taxes now instead of later?

While there are many reasons why you might want to consider this, the two most common ones are tax rate arbitrage and withdrawal flexibility in retirement.

Tax Rate Arbitrage

Some folks have income that is variable from year to year, either because the income from their work itself is variable or because in a particular year they have some kind of life event that makes that year’s income lower than a typical year. (And when some people retire their taxable income becomes much lower because they are spending from savings and taxable brokerage accounts.) In years where your income is enough lower that you are in a lower marginal tax bracket, then a Roth conversion can make sense because the tax you pay will be at a lower rate than it normally would. Similarly, some folks for a variety of reasons might be in a higher marginal tax bracket in retirement than they are when working (pensions combined with RMDs, an inheritance of retirement accounts with RMDs, etc.), so it could make sense to pay taxes now at a lower rate.

Withdrawal Flexibility in Retirement

People who have done a good job of saving and investing in traditional, pre-tax retirement accounts may face a “problem” when it comes time to take withdrawals from those accounts. (To be sure, this is a good problem to have.) Specifically, there are Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from traditional retirement accounts that currently being at age 73 (and will increase to age 75 in 2033). Those RMDs are determine by law so you have to take them whether you need them or not, and sometimes can be large enough that they push you into a higher marginal tax bracket. Which is the opposite of tax arbitrage, the amount you saved on taxes when you contributed could actually be less than the taxes you pay when you withdraw. That’s not ideal. There are also additional impacts of having a higher income in retirement such as the impact on IRMAA (discussed below).

Filling Up Your Tax Bracket

If it makes sense for you to do a Roth conversion in the context of your entire financial plan, then a typical technique is to “fill up your tax bracket.” Our federal tax system is a progressive system, which means different amounts of income are taxed at different rates. Your marginal tax rate is the rate at which your highest dollar of earnings is taxed at. Tax rates are applied to tax brackets, so every dollar of income over the low end of your marginal tax rate bracket is taxed at that rate. But it’s also important to be aware that every (potential) dollar of income above your highest dollar of earnings will also be taxed at that same tax rate until your income reaches the bottom of the next tax bracket. Here are the tax brackets for the 2025 tax year.

For example, if you are married filing jointly and your taxable income is $90,000, then your marginal tax bracket is 12%. This means that your highest dollar is taxed at 12% (12 cents of taxes), as well as every dollar over $23,850. (The first $23,850 is only taxed at 10%, so 10 cents for every dollar). It also means that you have $6,950 “left” in the 12% tax bracket (the difference between the $96,950 top of the tax bracket and your $90,000 of taxable income). That $6,950 room left in the 12% tax bracket can sometimes be used for tax optimization strategies. So for this example, “filling up the tax bracket” would be finding ways to increase your income by as much as $6,950. Any additional dollar over that would be taxed at 22%, which isn’t bad, but isn’t as good as 12%. One way to “increase your income” to “fill up your tax bracket” is through Roth conversions.

So What’s the Strategy?

For some people, at some times in their lives, doing a Roth conversion allows them to lock in a lower tax rate than if they waited and withdrew it in retirement. When that is the case, and if other factors don’t come into play, then calculating the amount of room left in your marginal tax bracket and then doing a Roth conversion in that amount to “fill your tax bracket” can make a lot of sense.

Other Factors

You have to careful, however, to consider your entire tax situation, not just look at your federal tax bracket when considering Roth conversions. Because Roth conversions are classified as earned income in the year you take them, they can have other (negative) impacts on your finances. While there are many ways this can happen, these are four of the most common ones to watch out for.

- State Taxes: If you live in a state with a state income tax, and if your state income tax is also a progressive system, you will want to see if the Roth conversion might possibly change your state marginal tax rate. If it does, that doesn’t necessarily make it a bad idea, but you need to do the math. For example, if the Roth conversion pushes you into a higher marginal tax bracket for state taxes, but the increase on your highest dollar is only 1%, and you are saving 10% on your federal taxes (the delta between 22% and 12%), then you still come out ahead. (If you live in a state with no state income tax, or a state like Colorado with a flat income tax, then you don’t have to worry about this one unless you think you might move to a different state in retirement.)

- Student Loans: If you have federal student loans and are in an income-based repayment plan, your monthly payments are based on your taxable income. Because Roth conversions increase your taxable income, they could also increase your student loan payments. This is effectively an additional “tax” that can partially (or fully) offset the savings from doing the Roth conversion.

- Health Insurance through the ACA: If you get your health insurance through the Affordable Care Act, the amount you pay is based on your taxable income. If you do a Roth conversion, your taxable income increases, and therefore so will your health insurance premiums. Again, this is a “tax” that can offset the federal tax benefits of the Roth conversion. (This will be even more of a factor as the current Administration is not a fan of the ACA and is letting the expanded subsidies that started during the Biden Administration lapse after this year.)

- IRMAA: Once you are on Medicare you pay a monthly premium (starting at $185/month in 2025). But this premium can increase based on your income. So, once again, a Roth conversion increases your income, and if it increases your income above a particular IRMAA threshold, then your monthly Medicare premium will increase. Which, again, could outweigh the federal tax savings.

But since many times none of those apply or, when they do, it’s still a net positive (especially when looking out toward the time when you have to take RMDs), Roth conversions are still something to take a look at toward the end of each calendar year. (Typically you want to do it toward the end of the calendar year so that you have a good idea of what your total income for the year will be, which then allows you to calculate how much room you have in your tax bracket more accurately.) One other thing to keep in mind is that your tax liability for the year will increase due to the Roth conversion, so you will want to adjust your tax withholding if you can (or perhaps make an estimated tax payment) in order to avoid any possible penalties.

An Example

So I’ll use our situation as an example. When we were working we were in the 22% marginal tax bracket, and now that we are retired we are still (currently) in the 22% marginal tax bracket. So, on the surface, it may not seem like an ideal situation for Roth conversions. Not that they would necessarily be “bad”, just that there isn’t a huge advantage. And, in fact, right now we are not doing them. But that’s because we are currently getting our health insurance through the ACA Marketplace, so doing a Roth conversion now would not only increase our taxes but would also decrease our subsidy (and therefore increase our health insurance premiums). But three things are going to change soon (and one more a bit in the future) that are (likely) going to lead to us doing Roth conversions.

- End of the Expanded ACA Subsidies: The current Administration is very unlikely to extend the expanded ACA subsidies. When that happens, we will no longer qualify for subsidies and insurance through the Marketplace will be more expensive than through our pension plan. So that removes one “negative” from the analysis.

- Inheriting a Traditional IRA: My Mom is about to turn 96 and has a decent-sized (not huge) traditional IRA that will get split evenly among myself and two siblings. Inherited IRAs have required RMDs starting in year one, and the entire amount has to be taken out within ten years. Those RMDs probably won’t push us into the next tax bracket, but they will definitely get us much closer.

- IRMAA: We are currently 61. We still start Medicare at age 65, and IRMAA has a two-year look back (so the first year of Medicare it will look at our income the year we were 63). That means next year (when we are 62) is the last year before we need to think about the IRMAA limits.

- Our Own RMDs: For our own traditional IRAs (which are reasonably large), RMDs will start when we turn 75. While that’s still a bit in the future, when that happens they very well could push us into the next tax bracket as well as require us to pay more for Medicare premiums due to IRMAA.

There’s also a fifth factor which is that our current expectation is that we will need to use very little of our retirement accounts for ourselves because we are comfortably living on our pensions, will have small Social Security benefits kick in around age 67, and will likely have a small (but still meaningful) inheritance from my Mom. Therefore we are not only thinking about our potential taxes, but our daughter’s potential taxes when she inherits money from us. While it’s really difficult to predict what marginal tax rate she will be in whenever that happens (due to both what tax policy will be as well as what she is earning at that time), all things being equal it will be easier (and more certain) if she inherits already-taxed assets (Roth IRAs and taxable investments) over traditional (pre-tax) accounts. While it’s certainly possible that she would be in a lower tax bracket, in which case the truly optimal solution would be for her to inherit traditional, pre-tax accounts, we’d rather lock in today’s historically low tax rates as well as simplify any tax complications when she inherits. Roth conversions help us accomplish this, while at the same time lowering our own RMDs at age 75, which will either keep us from moving to the next tax bracket or at least minimize the amount that is taxed at the next tax bracket.

Our Current Thinking

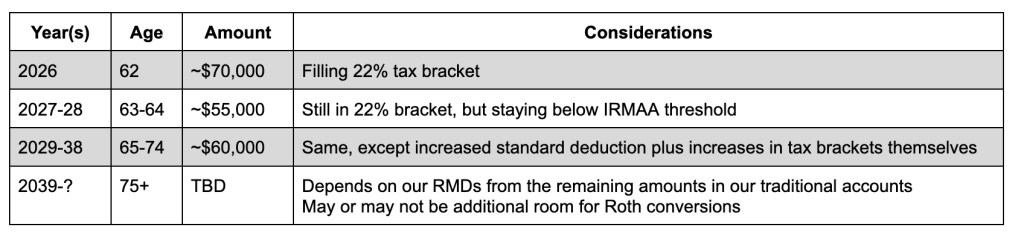

Lots of things could (and likely will) change, of course, but just because things are going to change doesn’t mean you can’t do some advanced planning and then adjust as circumstances change. To be clear, I’m not suggesting this is the only approach or even the best approach, but I think it’s a good example of one way to think through this.

Addendum 8-3-25: For some additional considerations read Vanguard’s “A BETR Approach” (pdf). In particular, note the additional tax savings (and compounding) when you use taxable accounts to pay the tax on the conversion (which you always should). I did not include that in my original considerations, but that makes Roth conversions even a bit more attractive. You might also check out Vanguard’s Roth Conversion calculator.