Roth Conversions are a topic that comes up occasionally so I thought I’d talk a bit about how we currently think about this. For those who aren’t familiar, a Roth Conversion is when you take some of (or all) the money that is currently sitting in a pre-tax IRA/401k/403b/457b and move it to a Roth account. This moving is officially called a conversion, because when you move it you also end up owing taxes on the amount you moved since you are moving it from pre-tax to post-tax. People might want to do this to try to attempt to lower the lifetime taxes they pay or simple to increase their flexibility in retirement by having some pre-tax money and some Roth money.

The typical way people have thought about this is that it’s a good idea to do this if you expect to be in a higher tax bracket when you withdraw the money than you are now. The thinking is (and it’s correct as far as it goes) that it’s better to pay taxes now at a lower rate than taxes later at a higher rate. (A reminder that there is no mathematical difference between a Roth account and a pre-tax account if you are in the same tax brackets when you contribute and when you withdraw). It can also be a good idea if you think you might be in the same tax bracket but want to better manage the eventual Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) that you have to take from pre-tax accounts (but not from Roth).

But Vanguard recently released a report titled, “A BETR Approach to Roth Conversions” (pdf) that provides a bit more of a nuanced look at this decision. (“BETR” stands for “break-even tax rate” and we’ll discuss it more below.) While they agree that future tax rate expectations are part of the decision making progress, they identify three additional factors that people should consider:

- When the conversion tax is paid from a taxable account.

In such a case, the longer the investment horizon, the lower the BETR. - When the traditional IRA includes nontaxable basis.

- When the conversion of the traditional IRA opens the “back door”

to future Roth contributions.

The second and third reasons only apply to a minority of people and don’t apply to us, so I’m just going to focus on the first reason. Vanguard argues (and provides the math) that a big factor in whether to do a Roth Conversion is not just your current and future tax rates, but critically where you get the money from in order to pay the conversion tax. You basically have four choices for where to take the money to pay the taxes:

- From your traditional pre-tax account (taking part of the conversion to pay the taxes), which results in less ending up in your Roth account.

This is rarely if ever recommended. - From your taxable investment account that is invested in a tax-efficient portfolio.

- From your taxable investment account that is invested in a tax-inefficient portfolio.

- From a taxable account that holds cash and cash equivalents.

Like a high-yield savings account or a money market account.

The further you move down that list, the more likely a Roth conversion makes sense, because the less tax efficient the money you are using to pay the taxes with now is the lower the total lifetime taxes you will pay. Sometimes (but not all of the time) that means even if you aren’t in a higher tax bracket when you distribute the money it can still make sense to do a Roth Conversion. Read the report if you want all the details (and more specifics on the math), but we’re just going to proceed with that in mind. Conveniently, Vanguard provides a free online calculator so you don’t have to do the math yourself. The data I’m going to share below comes from this calculator.

To make this more concrete, I’m going to share some of our numbers and my current thinking around how to approach this. In order to do this analysis for yourself, you need to know some numbers for the current tax year (the year you are thinking of doing the conversion), as well as make some assumptions about the future. Here are the numbers you need to know and the assumptions you’ll need to make:

- Taxable Income for the year of the conversion.

- Your current federal marginal tax rate for the year of the conversion (based on your taxable income).

- Your current state marginal tax rate for the year of conversion (if any).

- Your future taxable income at distribution.

- Your guesstimated marginal federal and state tax rates for the year of distribution (the year you anticipate beginning to withdraw the money from the Roth).

Note that the calculator assumes you withdraw it all in that year so is actually underestimating the potential benefit. It also assumes that tax rates stay static through this period. - The amount you might want to convert.

Note that you can play with this number and that I’ll share our strategy for determining this number below. - How many years from the time of conversion to the time of distribution from the Roth account.

- How you will pay the taxes on the conversion (from the pre-tax IRA, efficient taxable investment account, inefficient taxable investment account, or cash and cash equivalents).

- Your assumed capital gains and qualified dividends tax rate (0%, 15% or 20%).

- Your assumed annual return on investments.

- Your assumed dividend yield on taxable investments.

- Your assumed interest rate yield on cash and cash equivalents.

That may seem like a long and daunting list, but it’s really rather straightforward, and you simply enter those numbers into the calculator and it does the rest. For example, here are the numbers I used for our situation (with some variation for different scenarios):

- Taxable Income: $125,000

- Current Federal Marginal: 22%

- Current State Marginal: 4.4%

Colorado has a flat tax of 4.4%. - Future Taxable Income at Distribution: $150,000

I chose this as “more” than the $125,000 current, but what matters is what marginal tax bracket this puts you in at distribution. So no matter what number you put here, you can “override it” by putting in a different marginal tax rate below. - Estimated Federal and State Marginal Tax Rates on Distribution: Same, 22% and 4.25%

- Amount to Convert: $86,400

I’ll talk more about where this number comes from as well as some alternate numbers we will consider. - Number of Years Until Distribution: 20

Although the calculator automatically shows out to 50 anyway. - How Pay the Taxes Now: Cash and Cash Equivalents

In effect we would be moving the amount of tax paid on the conversion from our taxable accounts to our Roth accounts. It’s like being able to choose to make extra Roth contributions. - Capital Gains/Dividend Tax Rate: 15%

This doesn’t factor in for my example because we are using cash/cash equivalents instead of taxable investments that might have dividends and capital gains. - Assumed Annual Return on Investments: 7%

- Assumed Annual Dividend Yield: 2%

Although this also doesn’t factor into this calculation since I chose Cash. - Assumed Interest Rate Yield on Cash: 4%

This is a bit higher than what you can get right now and a bit higher than the long-term expected return, but choosing a slightly higher number here is actually the more conservative assumption for the calculation (because a lower cash return would increase the asset difference in the end).

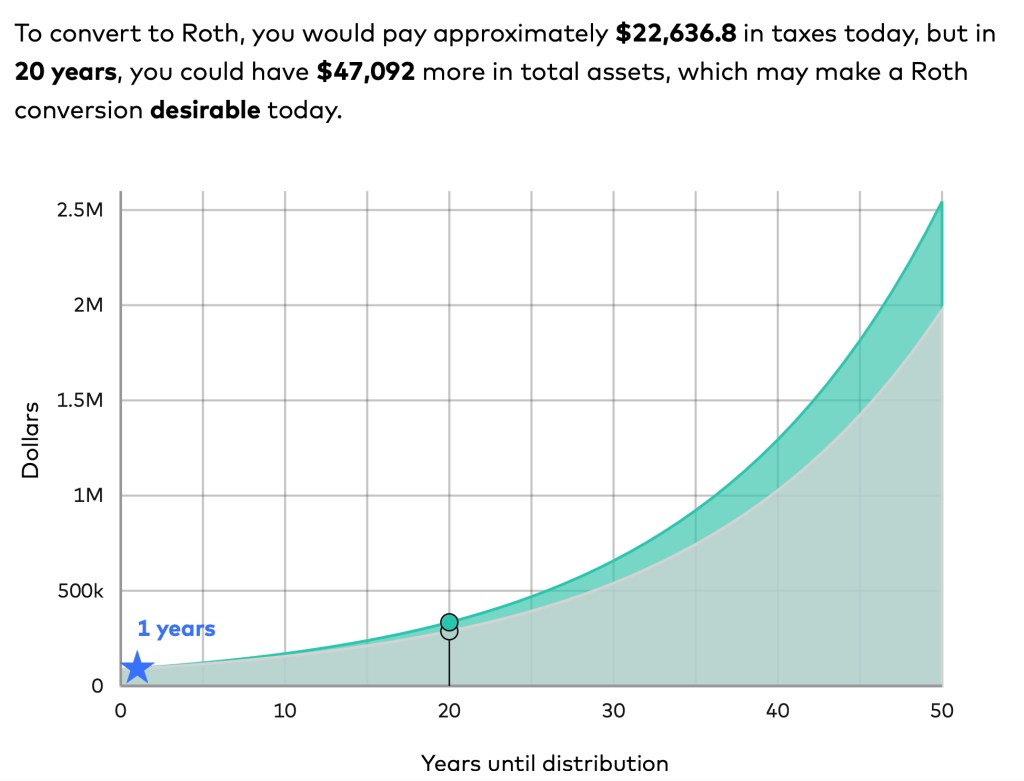

When you enter these numbers into the calculator it gives you two really interesting pieces of information. First it gives you a chart showing your asset growth year by year if you don’t do a Roth conversion compared to if you do. In the chart below, the top line (higher after-tax assets) is if we do the Roth conversion, the bottom line is if we leave the money in the pre-tax account. The star at 1 year indicates that is how long it takes to come out ahead by doing the conversion. Again, this calculator assumes a full liquidation at any point on this chart, so if you only do a partial liquidation and leave some of the money invested in the Roth for longer, it will continue to grow faster than if you had not done the conversion (making the conversion even more beneficial than the chart indicates).

For example, for the specified 20 years we would have $287,249 (after tax) if we left it in the pre-tax account versus $334,341 (after tax) if we do a Roth conversion, an advantage of $47,092 from doing the conversion. If you look out further than 20 years the difference grows ($118,135 after 30 years, $266,496 after 40).

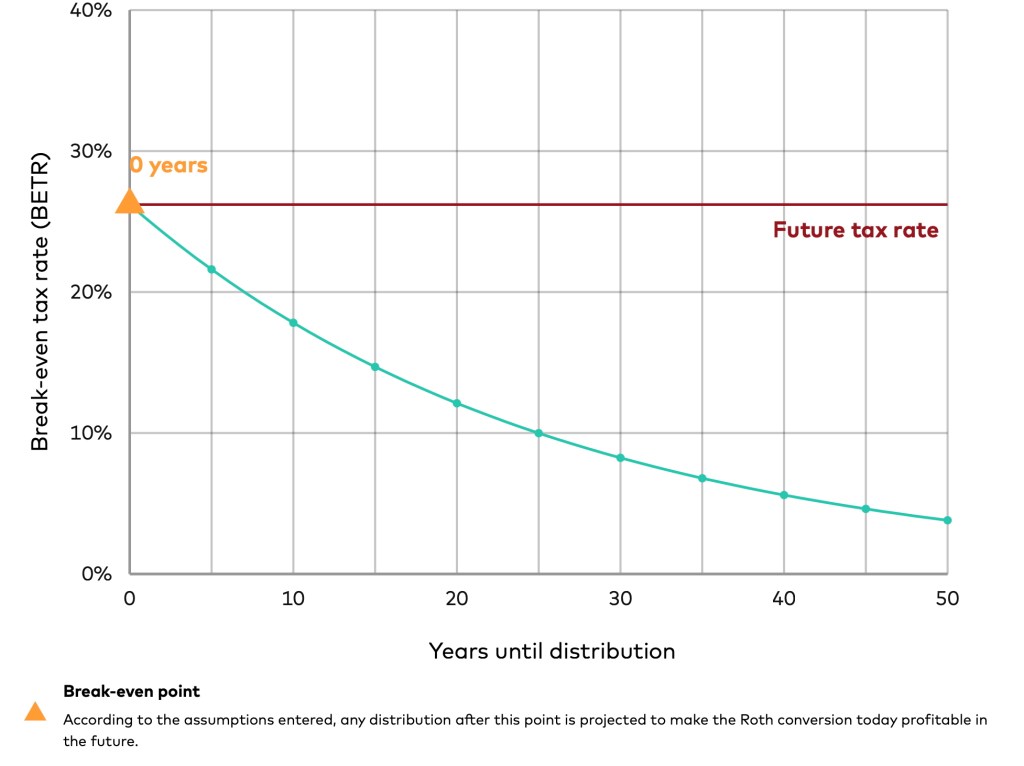

There is also a second tab on the calculator labeled the “Break-even tax rate“. Here’s what that chart looks like for this example.

At the specified 20 years, the Break-Even Tax Rate (BETR) is 12.11%. That means that as long as our current marginal tax rate (combined federal and state) is more than 12.11% in 20 years, we will come out ahead. The further out you go, the better it gets (8.24% at 30 years, 5.60% at 40). (So if we assume Colorado’s flat tax of 4.25% doesn’t change, that means we come out ahead as long as our federal marginal tax rate is more than 7.86% after 20 years, 3.99% after 30, and 1.35% after 40.)

As you can see, this is a much more nuanced view than “a Roth Conversion is a good idea if my future tax rate will be higher than my current tax rate.” In this example, our future tax rate could be significantly lower than our current tax rate and we would still come out ahead (hence the moniker “a BETR approach”).

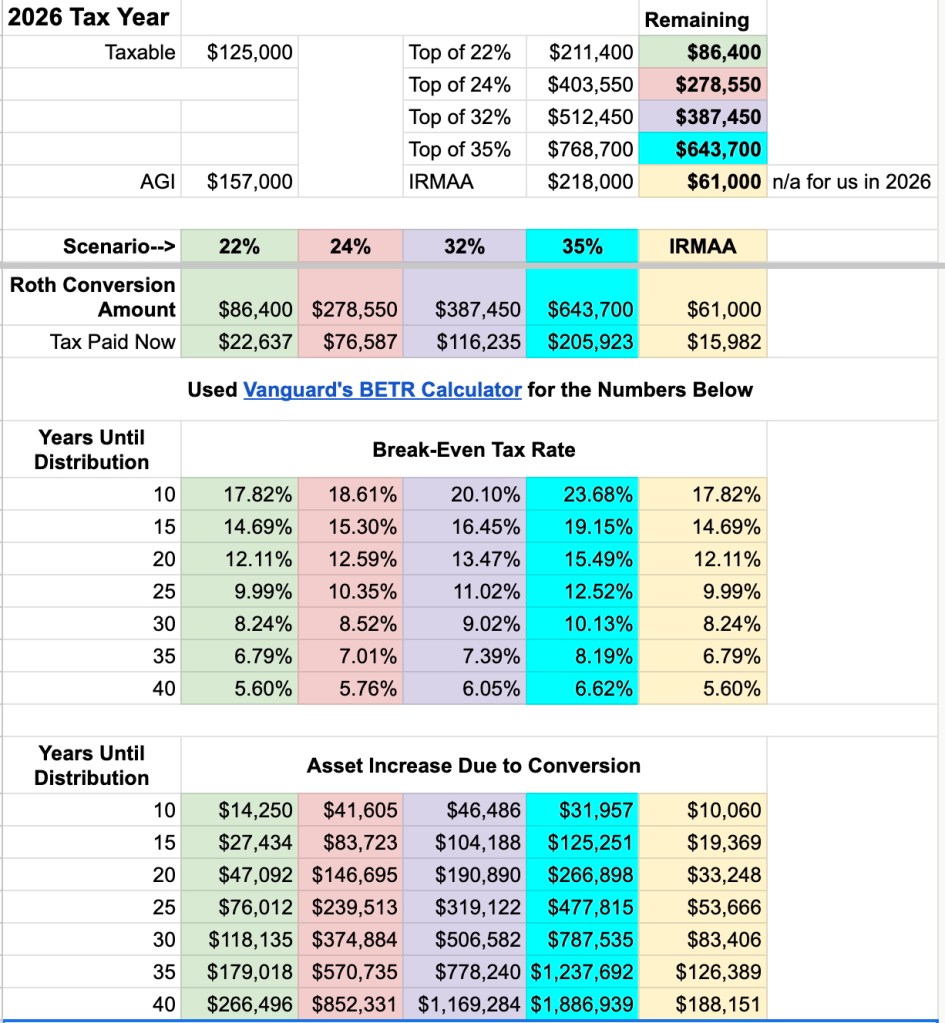

So where did the example conversion amount of $86,400 come from? That’s the difference between our taxable income and the current top of the 22% marginal tax bracket. By “filling the bracket” we are maximizing the amount we can convert at 22% without dipping into the 24% tax bracket (although more on that below).

What about the 20 years until distribution? Well, in many ways, the number you put in doesn’t make that much difference since the calculator shows you out to 50 years. But I used 20 for this example because that seemed like a reasonable number for many folks until they might start accessing their Roth accounts, as they likely will want to draw down their pre-tax accounts first (there are exceptions to this of course). For us, the number is likely (hopefully) going to be much greater than 20. Our joint life expectancy (time until the second one of us dies) is around 30 years. Because at this point we don’t anticipate needing our Roth accounts at all, they will likely go to our daughter who will then have 10 years before she has to take a distribution. So the probable number of years until distribution ranges from a minimum of 10 (if we both die the day after the conversion) to 40 or so (if one of us lives for 30 more years, plus the 10 years for our daughter as beneficiary to take the distribution).

It’s important to take a moment to talk about how accurate this calculator is or isn’t. As always, projections are only as good as the inputs, and in this case the inputs include some numbers that are exact (our current taxable income, our current tax rates, how much we want to convert) and some that are assumptions (future tax rates, years until distribution, return on investment, return on cash). But one of the great things about this calculator is that the BETR tab is independent of future tax rates; the break-even tax rate is determined from a combination of the exact numbers we know now and the return assumptions for investments and cash. So while those return assumptions could obviously be wrong, if they are reasonably close than we can get a really good idea of how dramatically future tax rates would have to change in order for the conversion to be a bad idea. In this example I feel pretty confident that our future tax rates will be higher than the BETR and, if they do turn out to be lower, that’s not a bad thing because it means that while the Roth conversion would’ve turned out not to have been optimal, we will still be paying lower taxes on our taxable income at that point.

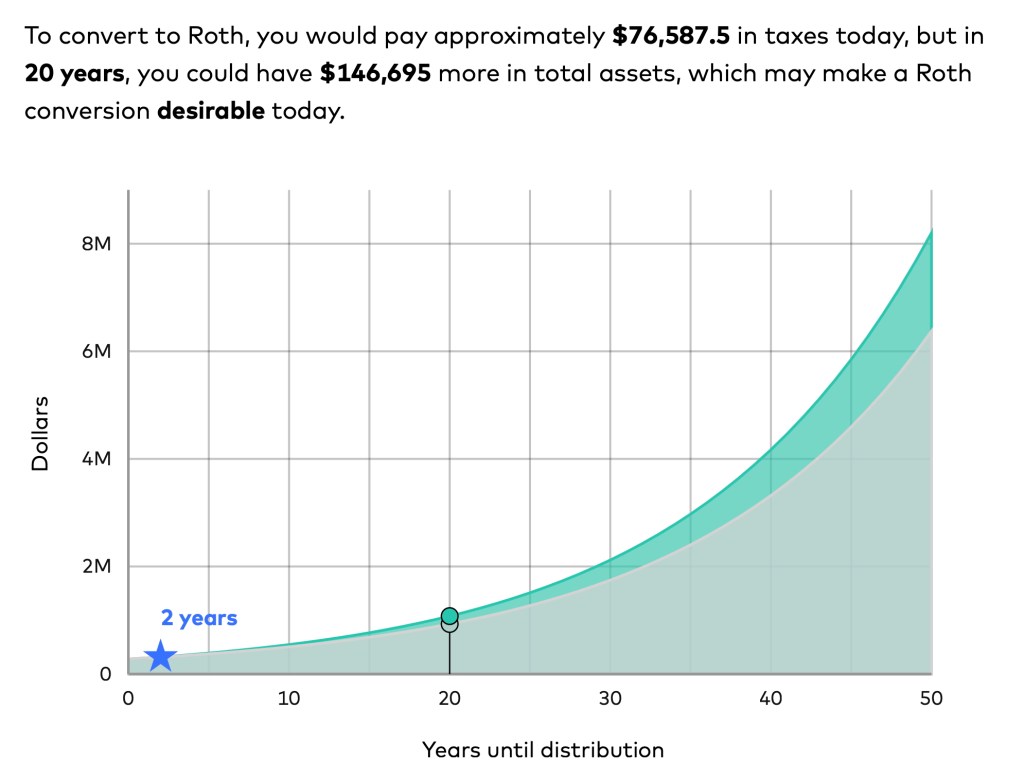

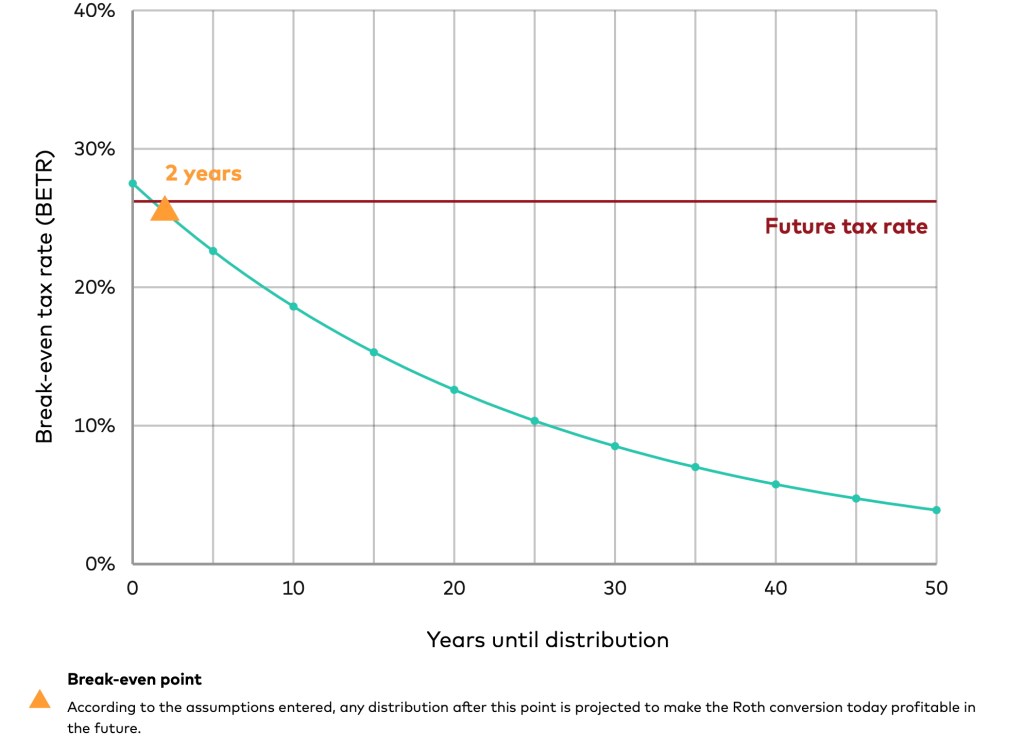

For this example I chose a conversion amount of $86,400 to “fill up” our 22% tax bracket, but what happens if we do go into the 24% tax bracket with some of the conversion? Well, with the calculator, that’s easy to find out. To fill up the 24% tax bracket we could do a really large conversion of $278,550. To get the calculator to give accurate results, however, you do have to do a little bit of math on your own, because the calculator assumes that your marginal tax rate is whatever rate your current taxable income is at without including the Roth conversion amount. In this case, the Roth conversion amount will take us into the 24% tax bracket, so that means the assumed 22% tax bracket would be incorrect. But entering in 24% would also be incorrect, because only part of the Roth conversion is taxed at 24% (the first $86,400 is taxed at 22%). So when you do the math ($86,400 x 22% + $192,150 x 24%), it comes out to a blended rate of about 23.3% for the entire amount, so that’s what we need to enter in the calculator. (Colorado’s flat tax means we don’t have to do a similar calculation for state taxes, it stays at 4.25%.) So here are the charts I get when enter in a conversion amount of $278,550 at 23.3% (everything else is the same as the previous example).

Perhaps surprisingly (for some folks), the break even point for coming out ahead in assets is only two years, and the BETR after 20 years is still only 12.59%. This means that assuming our rate of return assumption of 7% (nominal) for investments, and our return assumption of 4% (nominal) for cash are reasonably accurate, it would make sense for us to fill up the 24% tax bracket and make the much larger conversion. (Recall that the 4% return assumption for cash is actually a “conservative” assumption, as the likely yield will be lower than 4% which will increase the advantage of doing the conversion.)

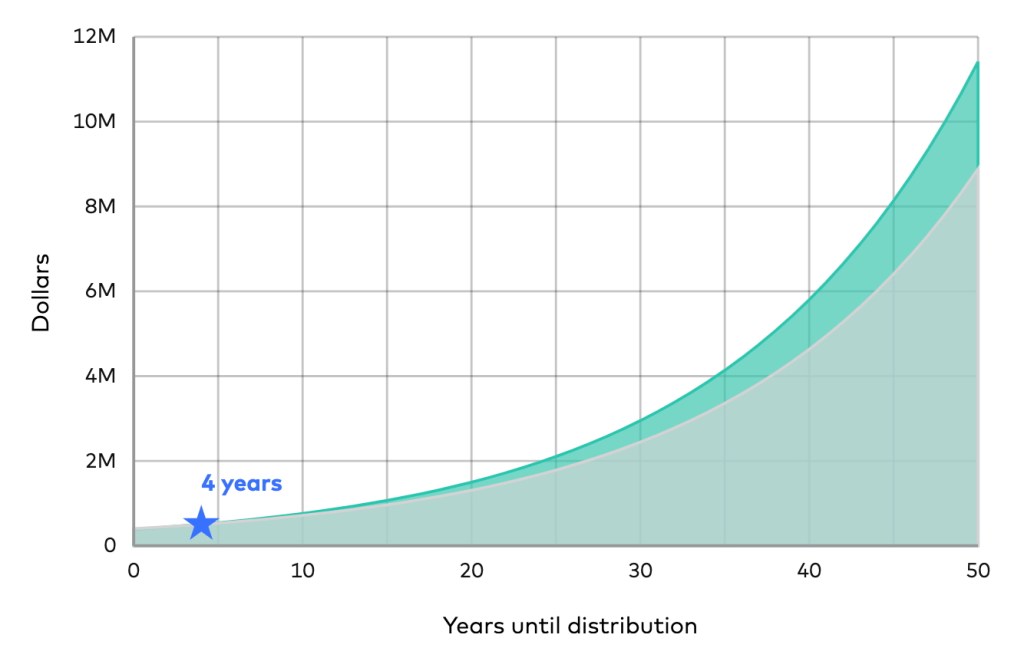

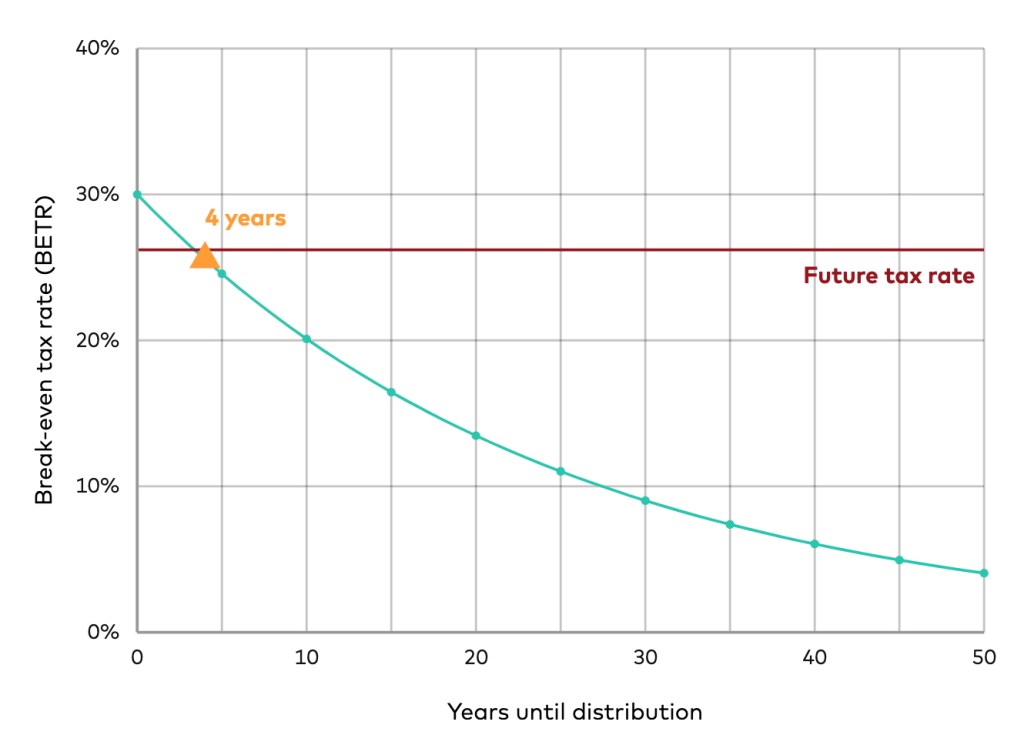

Well, what if we fill the 32% tax bracket? That would be a conversion amount of $387,450 with a blended federal tax rate of 25.8% (so paying a total of $116,235 in taxes now). Still looks pretty good.

Still only four years to come out ahead in assets and a break even tax rate (combined federal and state) after 20 years of 13.47% (9.22% federal), 9.02% (4.77% federal) after 30, 6.05% (1.80% federal) after 40.

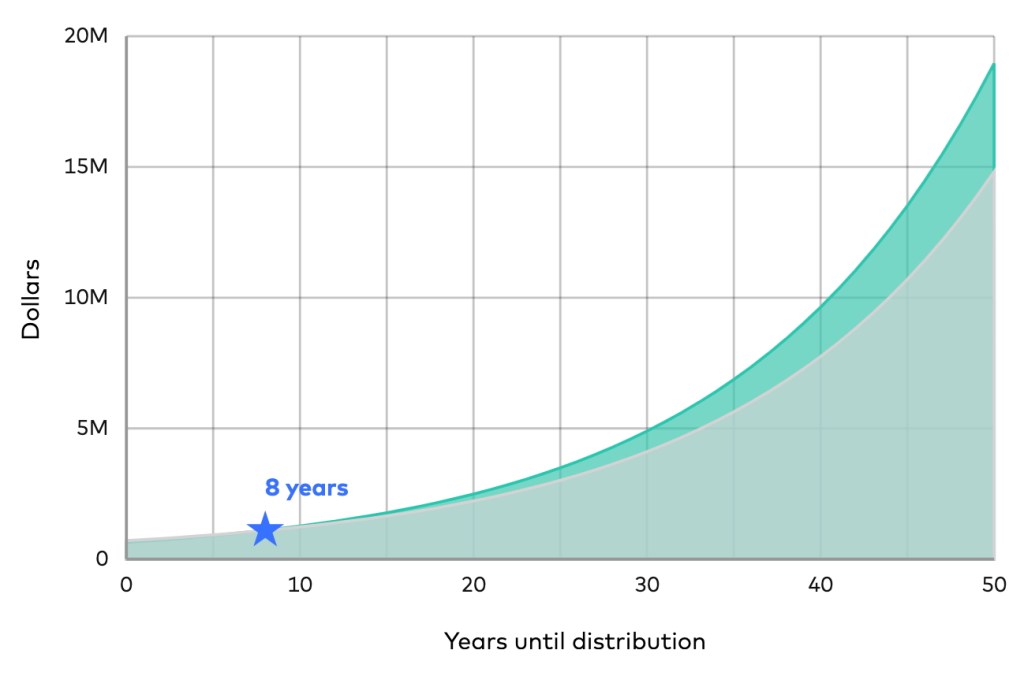

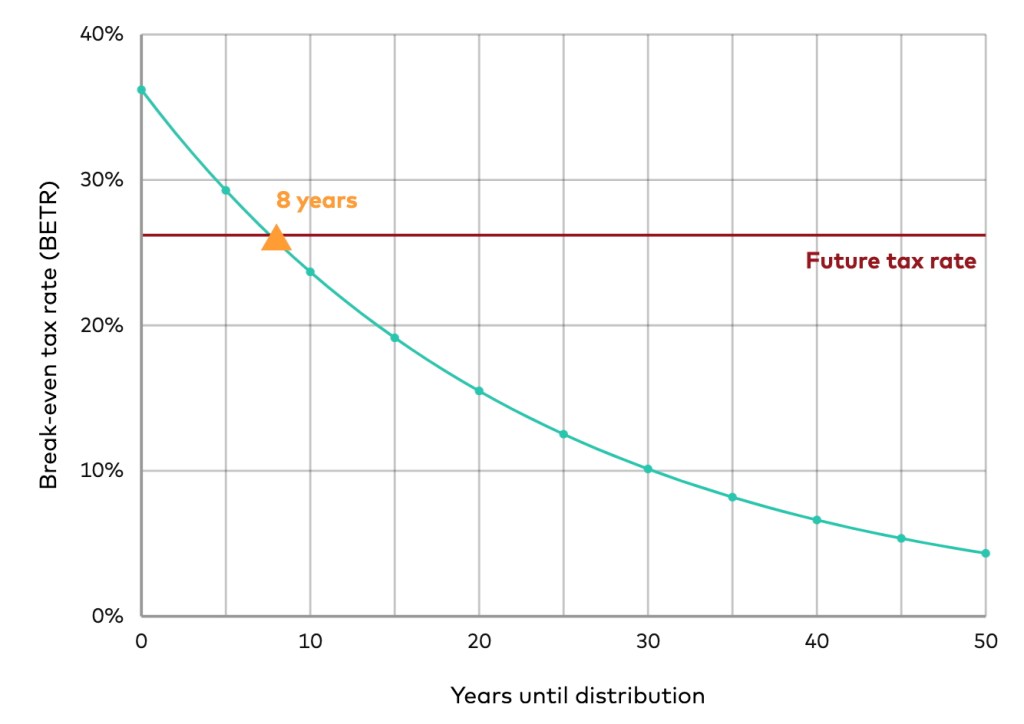

What about filling up the 35% tax bracket? That would be a conversion amount of $643,700 with a blended federal tax rate of 32% (so paying a total of $233,019 in taxes now). Still looks pretty good.

Now up to eight years to come out ahead in assets and a break even tax rate (combined federal and state) after 20 years of 15.49% (11.24% federal), 10.13% (5.88% federal) after 30, 6.62% (2.37% federal) after 40.

All of these are included in our Roth Conversion Decision Spreadsheet.

What if we went past 35% into the 37% bracket? Well, I’m not going to do that (although you could) due to a practical limitation for us: how much we have in cash and cash equivalents available to pay the taxes now. We don’t have enough to pay the taxes now at these really large conversion amounts without dipping into our taxable investments (not just cash and cash equivalents), which would then change the calculator inputs. You definitely could do the work to figure this out, but the calculator doesn’t get granular enough to make that easy and we aren’t going to make that big of a conversion.

So far it sure looks like doing a Roth conversion is almost a no brainer if you have the ability to pay the current taxes from cash and cash equivalents (and likely from taxable investments as well, but with a higher BETR). But as Vanguard acknowledges in their white paper, making the decision by only looking at the conversion itself can leave out some important constraints. While there are definitely other constraints, here are three that apply to us (and likely to a lot of other folks): possible ACA subsidies, IRMAA, and possible changes (typically increases) in future taxable income.

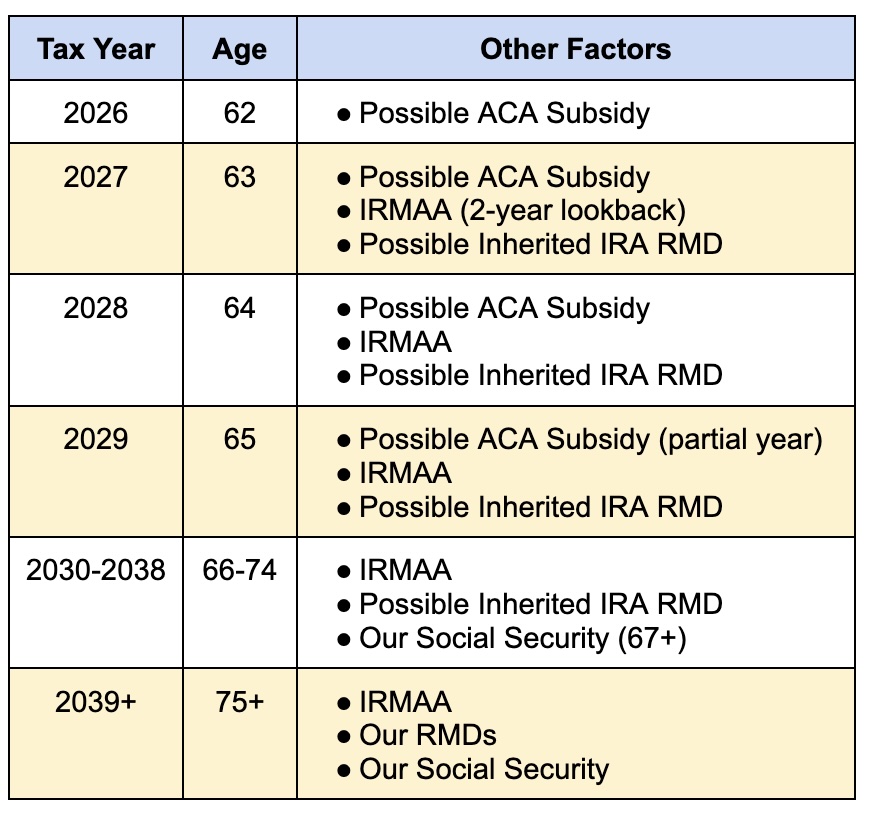

As I’ve written about previously, we have been receiving our health insurance the last few years through the ACA marketplace. We have been receiving a subsidy (actually a tax credit) based on our income (MAGI). The reason we haven’t been doing Roth Conversions these last few years is because a Roth Conversion increases your MAGI which would then decrease the ACA subsidy we receive. For example, the last few years our insurance premiums have been capped at 8.5% of our MAGI, which means if we do a Roth conversion it effectively adds 8.5% to our tax rate (so our 22% marginal federal tax rate effectively becomes 30.5%). (Note that it only adds 8.5% to the first ~$107,000 of conversion as any amounts over that would be over the amount where we would get any ACA subsidy.) As we saw in the examples above, that doesn’t necessarily mean we shouldn’t go ahead and do the conversion, as the calculator illustrates that even if we went to the 24% tax bracket (which would become 32.5% with the decrease in ACA subsidy) that it still works out. But it does give us pause about taking an action that increases our tax rate when we could perhaps simply wait a few years and do the Roth conversion without that impact. That’s because once we turn 65 and are on Medicare, we would no longer be on an ACA policy and the subsidy impact of a Roth conversion would disappear.

As it stands right now, however, we will not be receiving any ACA subsidy in 2026 because of the expiration of the current enhanced subsidies. With our MAGI, we won’t qualify for any subsidy (hence the 125% increase in our health insurance premiums for this year). But there is still a possibility that some form of extension might be passed for 2026 (presumably retroactive back to January 1st, but who knows). Those possibilities include a clean extension (we would get the same subsidy with premiums capped at 8.5% of our MAGI) or some modification where we might still get a subsidy but it would have a higher percentage (likely something like premiums capped at 9.5% or 10% of our MAGI). Until we know for sure we don’t want to commit to a Roth conversion. If nothing passes (or if something passes but it phases out before our income level), then we will almost assuredly do some kind of Roth conversion. Our current plan is to wait and see if anything passes and, if it doesn’t, then probably make the conversion in December.

One downside of waiting until the end of the year is tax withholding. If we end up doing a reasonably large conversion, our current tax withholding (both federal and state) will come nowhere near our tax liability. While that’s not a problem for us in terms of paying it (we have to pay it whether it’s through withholding or when we file our taxes), it can end up in us owing penalties. The rules for federal and the state of Colorado (pdf) are similar and, thankfully, there are some easy ways to avoid this. The easiest way to avoid this is to make sure you withhold more than 110% (for our income level) of our previous years’ tax liability (so for 2026 withholding, 110% of our 2025 tax liability). This is what we are doing, we’ve adjusted our withholding to make sure we withhold more than 110% of last year’s tax liability in case we end up doing this, and may even increase the withholding in the summer if it looks like there will be no ACA subsidies. (While you can also choose to make estimated tax payments, those also have to be made proportionally each quarter and we run into the same problem that we won’t know for sure that we will be making the conversion until possibly as late as December.) This works well for the first year of Roth conversions because we’re starting from a relatively low tax liability, but becomes more problematic if doing conversions several years in a row (because the following year it will be 110% of a relatively large tax liability). If the ACA subsidies aren’t extended for us this year, we will likely assume that will be the case going forward for the next two years before Medicare and simply withhold much more throughout the year in subsequent years.

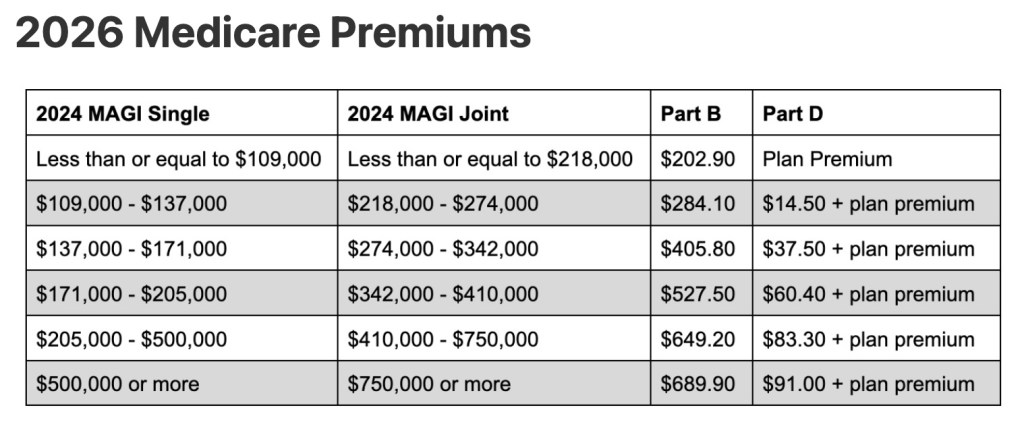

The second constraint for us (and for many others), is IRMAA (Medicare Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amount). Once we turn 65 and begin getting health insurance through Medicare, everyone pays a standard premium. But if you pass certain income thresholds, that standard premium can increase. For example, for 2026 if our MAGI is between $218,000 and $274,000, the Part B premium increases from $202.90 to $284.10 (a 40% increase), and the Part D (prescription drugs) premium increases by $14.50 (percentage varies depending on plan chosen). (Note that the chart indicates it is using your 2024 MAGI, because IRMAA is based on a two-year lookback. Also note that IRMAA is based on the higher MAGI, not taxable income.)

While those aren’t huge in terms of dollar amounts, they are still effectively an increase in tax rates (although relatively small increases when applied to the size of the conversion). IRMAA increases are a “cliff”, however, which means if you go $1 over a threshold you pay the full amount of the higher premium, so you definitely want to pay attention the various cliff levels.

Because of the two-year lookback, people who anticipate enrolling in Medicare at age 65 have to be aware of possible IRMAA implications the year they turn 63. So for us, IRMAA is not a factor for us for 2026 (because we’ll only be 62), but will be something we’ll look at each year after that. Because of that, I’ve included a column for IRMAA on the spreadsheet to demonstrate how much lower of a conversion amount we would need to do if we wanted to stay below the first IRMAA threshold of $218,000. Instead of being able to convert $86,400 (the amount necessary to stay within the 22% tax bracket), or the much larger amounts that take us into the 24% and 32% tax brackets, if we wanted to avoid IRMAA the most we could convert is $61,000 (still a good amount, but much lower). We will see what it looks like with next year’s numbers, but I suspect the impact of IRMAA will be small enough that we won’t let that limit us. (For example, for 2026 the additional ~$1,148 x two of us in Medicare premiums for the first tier of IRMAA would effectively increase a federal 22% marginal tax on the conversion to only 24.6%.)

The third constraint for us (and for many folks) is that our taxable income may change (increase) in retirement. Right now our taxable income comes from our two defined benefit pensions (which currently get a small 1% COLA each year), a small amount of self-employment income I make from teaching financial literacy classes and a small number of book sales, and whatever interest and dividends our taxable accounts generate each year. But there are easily foreseeable future events that will likely increase that income. First, we are likely to inherit a pre-tax IRA sometime in the next few years. Beginning the year after we inherit, we will be required to take annual RMDs for the next ten years (and exhaust the account by year 10). While the IRA is not huge so the distributions won’t be particularly large, they still will increase our taxable income for those years and “eat up” some of the “room” for Roth conversions before different tax bracket levels.

Second, we will start receiving some Social Security the year we turn 67. I have earned enough credits under Social Security to earn a small benefit but my wife has not. Because of this it makes sense for me to to start taking my benefit at age 67 and 2 months, because that’s when my wife turns 67 and will be able to receive her full spousal benefit. (Normally we likely would’ve waited until 70, but because she doesn’t receive anything until I start it makes sense for me to start when she turns 67. This is a great calculator to explore your Social Security options.) This won’t have a huge impact, but will again shrink the room for Roth conversions.

Finally, we will be subject to our own RMDs from our pre-tax accounts when we turn 75. These RMDs will increase our income and again lower the room for any possible Roth conversions. This is an interesting one because the more Roth conversions we do before 75 (and even after) the lower these RMDs will be.

Here’s a table that shows the possible year-by-year factors for our situation.

So we’ll see what happens with the ACA, but I suspect we will do some kind of Roth conversion this year (and possibly a really large one), and then use the spreadsheet/calculator to evaluate conversions each subsequent year. One of the reasons this is so attractive for us is that we have let some cash build up over the last few years, but even if we were using some of our taxable investments (with more favorable dividend and capital gains tax rates) it would still likely make sense for us to do some Roth conversions (and likely for many others). The BETR framework and calculator is a good tool to help make the Roth Conversion decision much easier for most folks and give them the confidence to make the move if the numbers indicate they should.

Important Note: This is not suggesting that Roth conversions are right for everyone. The reason our numbers look so good is in large part because we are paying the conversion tax with cash which has a low after-tax yield (and assumes it stays in cash for the duration of the comparison). The reason for having that much cash is because the rest of our portfolio is very aggressive (essentially 100% stocks) and having some in cash provides us some small returns that are not volatile and the money can be accessed no matter the condition of the market.

In fact, if we took that cash and invested in our taxable brokerage account in tax-efficient index funds and then held until our deaths (so that they get a step up in basis), then that would likely over-perform the Roth conversion strategy. But this does help protect against future increased tax rates, either due to changes in the tax code or due to one spouse dying and the high combined-RMDs being paid out to the surviving spouse who is filing as a single person (and could therefore be pushed into higher tax brackets). This also tends to be more beneficial for folks with large pre-tax accounts, who don’t need (or want) to spend the money now, and especially if they plan to leave a decent amount as inheritance to their heirs.

Someone on Bluesky asked if the same thinking applies to contributions to pre-tax or Roth, not just conversions. This was my response.

I think the easiest way to think about this is to focus on the actual amount that gets invested. To keep the numbers simple, let’s assume you are going to invest $1,000 in an IRA and that you have a 25% marginal tax rate (combined federal and state) at the time of contribution and distribution.

If you invest $1,000 in a pre-tax IRA then you get an immediate tax savings of $250 which can then be used in some combination of spending, investing in taxable accounts, or put in a savings/money market account. A crucial point, however, is that you really only have $750 invested in the IRA, as $250 of it will eventually be paid in taxes.

If you invest $1,000 in a Roth IRA then you forego the $250 in immediate tax savings, but you have the full $1,000 invested. You are essentially transferring $250 from taxable to Roth, so you are essentially investing “more” than if you put $1,000 into a pre-tax IRA.

This is why apples-to-apples comparisons of pre-tax to Roth use $1,000 into pre-tax and $750 into Roth (because they both require $750 after tax dollars), where the result will be exactly the same in the end.

A Roth Conversion automatically invests the “extra” $250 if you use taxable dollars to pay the conversion tax, which is why it comes out ahead.

LikeLike

I love this! It is something I’ve long known, but couldn’t quantify until now. It starts to make one think that even high earners in their 30s should be putting into a Roth 401k instead of a traditional 401k since that may beat the normal ‘tax planning window’ tax rate that people get from retirement until social security and RMDs kick in.

My only question is, what would the chart look like if you used the same asset returns instead of cash from the taxable account? The reality is, most people would have to sell other high earning investments to rebuild that cash. I’m sure that moves out the breakevens a little bit, but how much?

Cheers, Shaun Williams

LikeLike

It’s easy enough to put that scenario into Vanguard’s calculator but, yes, it will increase the BETR down the road. It becomes less of a “slam dunk” the more efficient your taxable investments are.

Also see my other comment about how contributions might be thought of a little differently than conversions.

LikeLike