Some of you will be too young to get this reference, but the title of this blog post is best if read like Jan Brady saying, “Marcia! Marcia! Marcia!“

You’ve probably noticed that the topic of inflation has been in the news lately. It’s been in the economic news, brought up in political campaigns, talked about on social media, and certainly talked about in financial literacy classes. While I’m excited to see such an important financial topic being widely discussed, I am underwhelmed by the level of discussion (and knowledge) that is being brought to bear. So while I’m under no illusions that this blog post will significantly change the state of affairs, I’m writing it anyway because I hope to use it as a resource for my classes (and perhaps some other folks can benefit as well.)

What is Inflation, Why is It Important, and What Causes It?

Put simply, inflation is a measurement of the rise in prices over time. If prices drop, it’s called deflation (or sometimes negative inflation). Another way to frame inflation that is sometimes more helpful is as the decline in purchasing power over time; something that used to cost $10 now costs $20, so $20 now only has the purchasing power of $10 then.

While obviously a decline in purchasing power seems important to you as an individual (and it is), why do all of these serious people talk about it so much in terms of the economy? Because inflation that is deemed “too high” (more on that later) can lead to people not saving enough money, because they know their money will buy so much less in the future. It also causes uncertainty in future prices, which can hamper both individual and business planning, decision making, and development. And because one of the ways that governments try to rein in inflation is by raising interest rates, it can then lead to disruptions in the economy, including unemployment and recessions.

There are many causes of inflation, and not everyone agrees on what in particular is causing inflation at any given time. The causes are generally divided into three categories: demand-pull (demand exceeds supply), cost-push (the cost of goods and services to produce what you buy increase), and built-in (which is really a catch-all category for the fact that people expect prices and wages will go up, so they do).

What’s the Right Amount of Inflation?

The generally agreed upon “right” amount of inflation is 2%. That’s the target for the U.S. Federal Reserve and for many other central banks around the world. But the interesting thing is there’s no empirical reason for 2% – it’s basically a made up number. Many economists “think” this is about the right level of inflation for the economy to grow without prices getting out of hand: it’s the “Goldilocks” inflation rate – not too high, not too low. But nobody really knows if it is the right amount, or even if the right amount might change over time as our world changes.

And the inflation number by itself, in isolation, is only part of the story. For example, the Federal Reserve has a “dual mandate” to keep inflation under control and to achieve maximum employment. Many people think they have at times overemphasized inflation at the expense of employment. (For example, while higher inflation isn’t a good thing, it doesn’t come close to the devastation that unemployment can cause families.)

And you also have to look at inflation in relation to wage increases. Would you prefer inflation to be at 2% and wage increases to be at 0.5%, or inflation to be at 3% and wage increases at 4.5%? Most people would pick the latter, even though it’s higher inflation. (And, notably, wage increases have again exceeded inflation in the U.S. recently.)

How Do We Measure Inflation?

The most common way to measure inflation (at least in the United States) is something called the Consumer Price Index, or CPI. (There are actually multiple versions of the CPI.) The basic idea is to take a “basket of goods and services” that most people need and spend money on, and then track the price changes over time.

While that may sound simple, there are a lot of variables involved. First, which goods and services do you include, and who gets to decide that? Second, the CPI uses a “weighted average” of those goods, giving more “weight”, so a larger portion, to some categories than to others. Third, how, where and when do you measure the prices? Prices, of course, can change throughout the year (the supply of apples increases in the U.S. in the fall, so the price goes down, the opposite of demand-pull inflation). So when should you measure this? (This is why the CPI uses words like “seasonally adjusted” which tries to account for these known price fluctuations.) And prices vary by geographic region and even within geographic regions (especially in a country as large as the United States), and do you measure the cost of the store-brand of milk or organic milk?

Which is why I’ve written previously that inflation is personal. After all, if the price of gasoline is included in the CPI (it is, although sometimes CPI is also reported without “volatile” items like gasoline), but you don’t own a car, or you own an electric vehicle, or you own a gas vehicle but only use it occasionally for longer trips because you walk, bike or take public transportation to work, then any increase (or decrease) in gas prices doesn’t directly affect you. (It can indirectly affect you due to cost-push inflation.)

As an aside, the price of gas tends to be everybody’s favorite indicator of how inflation is doing, even though it’s a relatively small component of CPI. My theory (echoed by others) is that this is because gas prices are printed on every fourth corner in 4000 point font, so we are constantly bombarded with the price of gas, even on days when we aren’t purchasing gas. That then gets combined with recency bias and availability bias and distorts our thinking.

I’m also very interested to see what will replace the price of gas as people’s primary benchmark in about 20 years or so, when most people are driving electric vehicles and those 4000 point font signs start disappearing. Maybe the cost of electricity in kWh?

Similarly, if the price of “housing” goes up, that’s going to affect people differently depending on their housing situation. Sometimes buying a house goes up a lot while renting only goes up a little (or vice-versa). Sometimes interest rates rise which means buying a new house with a mortgage just got a lot more expensive, yet folks who already own their house and have locked in their mortgage rate won’t see that increase. And, to complicate it further, for folks who aren’t taking on new debt, a rise in interest rates can be thought of as deflationary to them because they can earn more on their savings. (Don’t get too excited, though, as cost-push inflation from higher interest rates might wipe a fair amount of those increased earnings out.)

And there are many other categories that impact different people in different ways. In addition, even when inflation does impact you directly you can sometimes make choices to mitigate those price increases, for example perhaps eating less meat (or more chicken and less beef). That obviously impacts your life (in a negative way, at least from your perspective), but is it really “inflation” in terms of your overall finances? It depends.

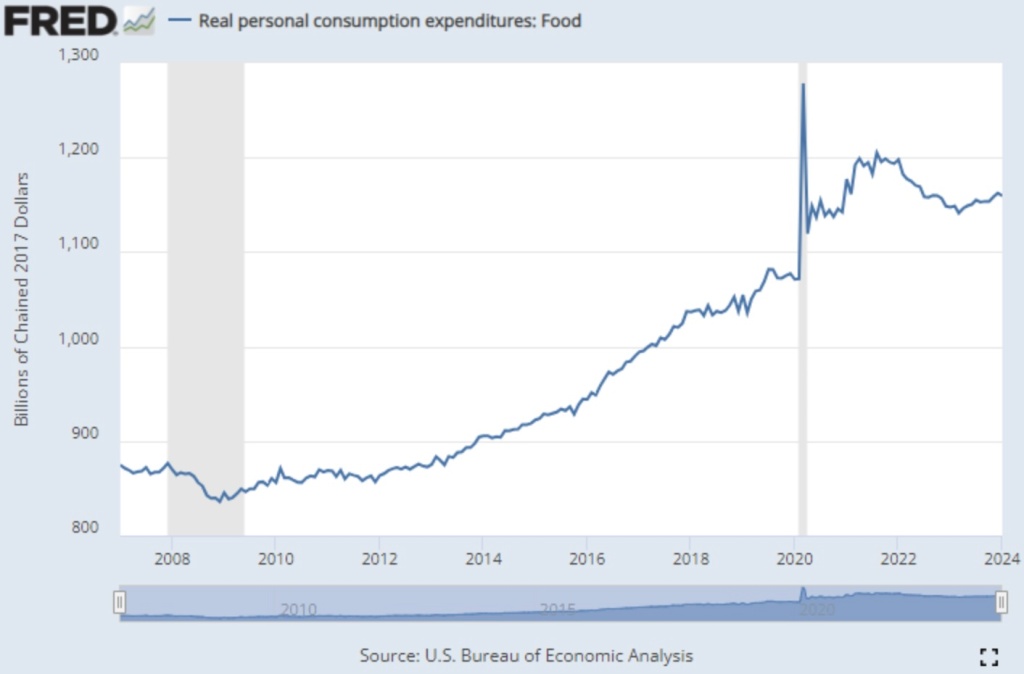

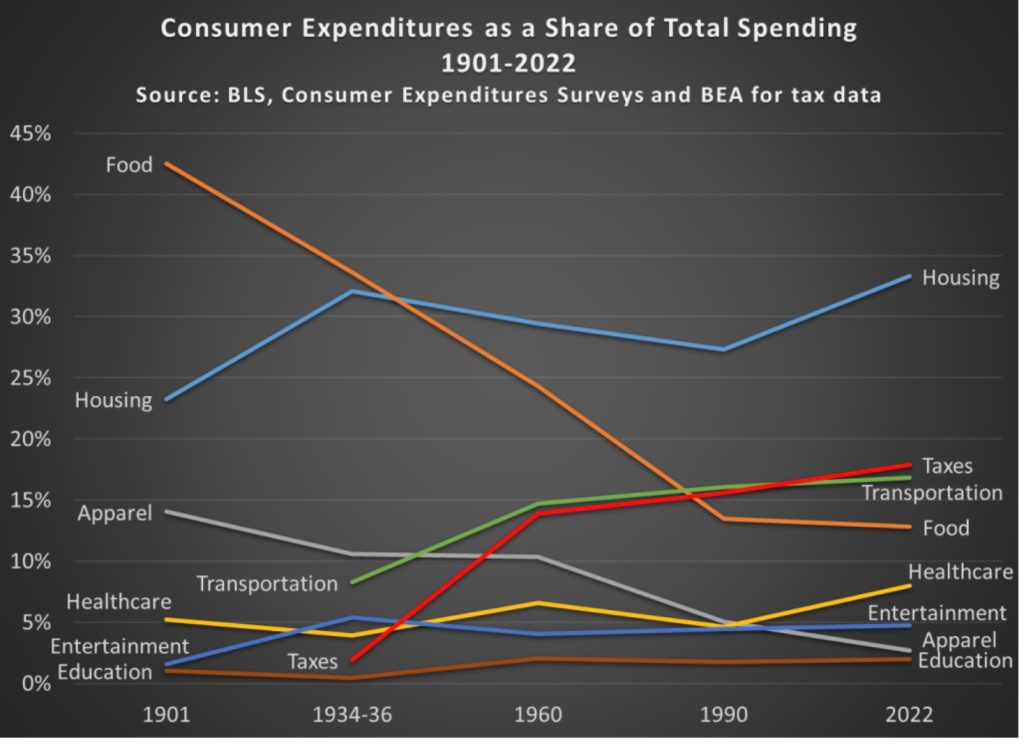

The cost of food is one of the big drivers of all these current conversations (perhaps because the price of gas has been declining lately). And there’s no question that the price of food has increased, the prices at the grocery store are up about 25% since the beginning of 2020 (which is a bit higher than the overall inflation which is up just under 21%). But the problem isn’t just the higher than usual increase in grocery prices (that 25% works out to an annual inflation increase of about 5%), it’s the choices that people are making. Take a look at these two charts (source):

The first chart shows that, even after adjusting for inflation, Americans are spending a lot more on food (otherwise it would be a flat line). How is that possible? Well, three main ways. We are likely buying more food, we are choosing to purchase more expensive items than we previously did (not more expensive due to inflation, more expensive because we are choosing products that were already more expensive), and – what the second chart is indicating – we are choosing to eat out a lot more. Inflation is personal. (And, for what it’s worth, we spend much less of our total income on food than we historically have.)

As another aside, part of the reason (not the entire reason) that both grocery store prices and especially restaurant meals are more expensive is because workers in those industries have finally seen some wage gains that have sometimes exceeded inflation. This partially makes up for their wages not keeping up with inflation for most of this century. So one of the questions you should ask yourself is, “Would I be happier with lower food prices if that means the people providing me that food are living in poverty?”

Why Has Inflation Been So High?

Despite the fact that I wrote that heading, I don’t think inflation has been “so high.” Yes, inflation definitely spiked higher than we would like (and to levels we haven’t seen recently) in 2021 and 2022. But that doesn’t necessarily (to me, at least) equate to “so high.” First, it’s important to look at why inflation spiked in 2021 and 2022. You may recall we had a global pandemic (and it’s not completely over). This caused huge demand-pull inflation (“supply-chain shocks”), which then led to cost-push inflation. It literally is unprecedented in our modern economic system (the flu pandemic in 1918 was horrible but was in a very different economic world that didn’t depend on global supply chains nearly as much). Second, this was followed by the war in Ukraine (which obviously is still going on), which also caused large demand-pull inflation in both energy and food prices (which then also lead to downstream cost-push inflation.) Governments also responded to the pandemic with stimulus money, which was definitely the right call but ultimately did likely contribute some to the spike in inflation.

Note: Some folks want to attribute inflation entirely to the stimulus, but the evidence points to the contribution from the stimulus to be a very small part of the spike in inflation compared to pandemic and war-adjacent reasons.

And context is always important. Sometimes zooming out can be really helpful, so let’s “zoom out” on inflation. Here’s a quick spreadsheet (of course) using historical inflation data in the U.S. since the year 2000.

It’s important to note that these numbers are different than some numbers you will see that talk about “average inflation” for the year, which averages each month’s inflation rate. But that number is pretty meaningless by itself, as it’s the year-over-year inflation you care about. The historical average inflation rate in the U.S. in the last 100 years is about 3.3%.

Column B shows the year-over-year inflation rate in the U.S. for each year from 2000 through 2023. So you can see that the inflation rate in 2023 was 3.4% (cell B25). Note the “outlier” higher numbers in 2021 and 2022 (7% and 6.5%, respectively). Those are the numbers that go everybody’s attention. But let’s zoom out.

- Cell H25 shows the annualized inflation rate if you go back 5 years: 4.1%. Certainly higher than we’d like (thanks to the P’s, pandemic and Putin), but not outrageous (it got as high as 13.3% in 1979).

- Cell K25 shows the annualized inflation rate for the last 10 years: 2.8%. Higher than 2%, certainly, but lower than the historical average.

- Cell N25: Last 15 years: 2.56%

- Cell Q25: Last 20 years: 2.59%

- Cell E25: Since 2000: 2.54%

How can this be? Well, if you look at the years 2008-2020, you’ll notice that inflation was very low, significantly lower than 2% much of the time (this was coming out of the Great Financial Crisis). Which means that in addition to the pandemic and Putin, some of the recent inflation is likely making up for those years of “too low” of inflation. At the time, many economists were actually concerned that we couldn’t get the inflation rate up to 2%, but of course most consumers didn’t think to celebrate what a great deal they were getting. We only notice when inflation is higher than normal, not lower.

What’s the Takeaway?

So what’s the point? Well, the point isn’t that higher inflation is good, or that it hasn’t had a meaningful (negative) impact on many people’s finances. It hits especially hard on those at the lowest levels of income. But my concern is that so many of the people who are complaining about higher inflation are not those people (most likely if you are reading this, you are not at the lowest levels of income). Yes, people with more income are definitely still affected, but not to such an extent that it should be used as an excuse for why they can’t make ends meet. When inflation was super-low from 2008-2020, they could’ve been getting way ahead, which then could’ve cushioned the impact of two years of higher inflation. And even during this time of higher inflation, wages have more than kept up (briefly not keeping up in 2021 and 2022). Here’s a chart comparing wages and groceries since 2010 (but, crucially, doesn’t show the spike since 2020.)

So my hope is that (for anyone who made it this far) folks try to arm themselves with actual data and some historical context (zoom out) instead of relying on the “feeling” that inflation is “so high” because you are anchoring on what milk or eggs used to cost (but somehow not anchoring on the fact that you used to make a lot less in income as well). So perhaps instead of saying, “Inflation! Inflation! Inflation!” you should say, “Data!, Context! Zoom Out!”

Thanks for the post, the long-term context of inflation is something I’ve been wondering about recently. It’s unfortunate CO Pera’s automatic increase is so low moving forward. Might be interesting to see a post about how to factor in the loss of buying power of my future Pera pension when retirement planning (if you haven’t already).

LikeLike

Well, the “good” news about the AI is that it will take a while before you feel the effects of it relative to inflation and, by the time you do, you’ve typically moved past the highest spending years. Spending in retirement is generally U-shaped. High at the beginning (the go-go years), then lower as you age (the no-go years), and then sometimes an uptick at the end due to medical expenses.

LikeLike